Guides

Carbon Footprint of a T-Shirt: Industry Benchmark based on 10,000 simulated lifecycles

T-Shirt Carbon Benchmark: 10,000 Simulations Reveal What Really Matters

Everyone talks about sustainable cotton. But the data tells a completely different story about where T-shirt emissions actually come from, and it's not what most brands want you to focus on.

Ask ten sustainability experts how much carbon a T-shirt produces and you'll get ten different answers. Some say 2 kg. Others say 15. A few will confidently quote "about 8" without telling you where that number comes from.

The truth is, there isn't a single number. The carbon footprint of a T-shirt depends on what it's made of, where it was manufactured, how it gets to you, and, crucially, how you wash it for the next three years. The problem with most benchmarks is that they pick one scenario and present it as the answer. A conventional cotton T-shirt made in China, washed 25 times, line-dried in Europe. Done. 8.77 kg. Next question.

But that single number hides a distribution. It ignores the organic cotton tee from Portugal that comes in at under 2 kg. It ignores the fast-fashion tee that gets tumble-dried twice a week in Texas and racks up 14 kg. It ignores the fact that what you do after you buy a T-shirt matters more than what it's made of.

So we decided to model the full picture. Not one T-shirt, ten thousand of them.

Key Findings

Median carbon footprint: 5.4 kg CO2e per T-shirt (cradle-to-grave)

90% range: 3.8 to 7.8 kg CO2e

#1 contributor: Manufacturing (49%), mostly heat and steam, not electricity

#1 source of uncertainty: Consumer behavior (64%), tumble drying is the single worst thing you can do

Sustainable brands vs fast fashion: 64–73% lower footprint. The gap is real.

How We Built This Benchmark

We used Monte Carlo simulation, the same statistical technique used by climate scientists, financial risk analysts, and pharmaceutical researchers when a single answer isn't enough. The idea is simple: instead of calculating one T-shirt, you calculate thousands, each with slightly different parameters drawn from realistic probability distributions.

Each of our 10,000 simulated T-shirts was assigned a random combination of materials, factory location, consumer market, garment weight, number of wash cycles, and disposal pathway. Not arbitrary random, weighted by real-world market data. A T-shirt is 6x more likely to be made in China than in Portugal, because that's what global trade data tells us. It's 3x more likely to be 100% cotton than polyester, because that's what Textile Exchange reports.

Every emission factor in the model is traceable. Material carbon intensities come from Ecoinvent 3.9.1, the most widely used LCA database in the world. Transport and waste factors come from DEFRA 2025, the UK Government's official greenhouse gas conversion factors. The methodology follows ISO 14040/44, the international standard for Life Cycle Assessment.

No invented numbers. No "industry estimates." Every value can be checked against its source.

What Does the Carbon Footprint of a T-Shirt Actually Look Like?

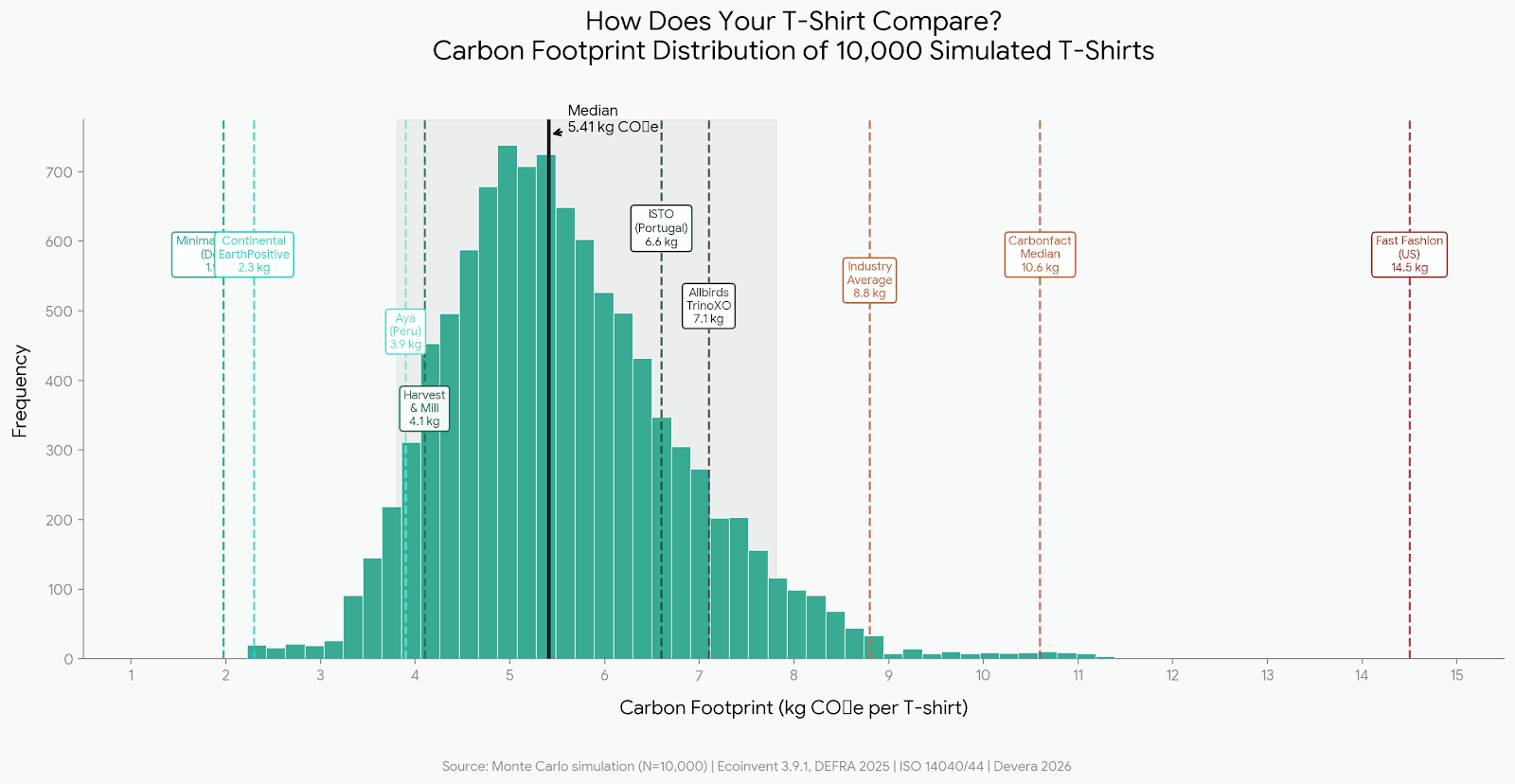

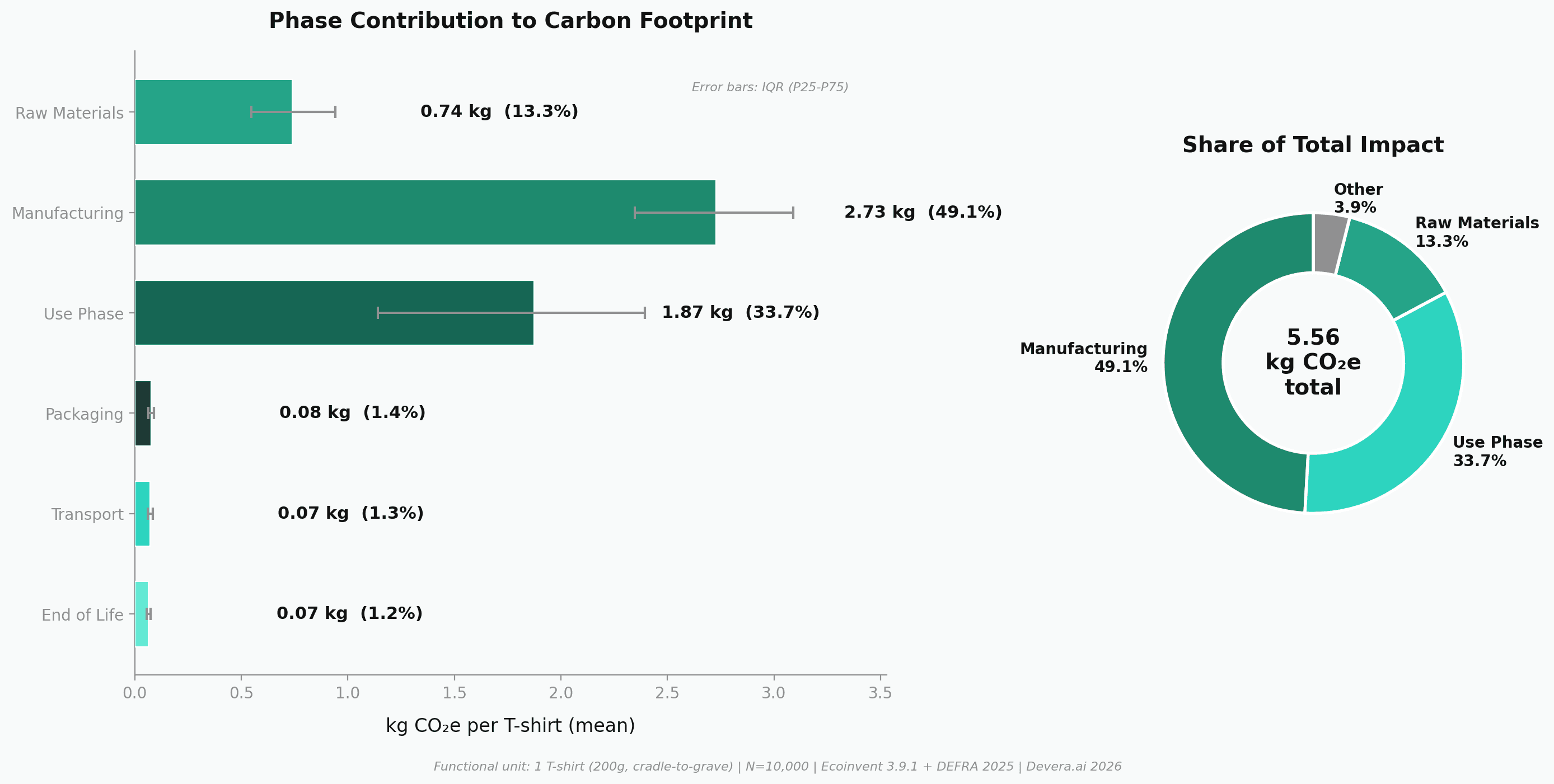

The headline number: the median T-shirt produces 5.4 kg of CO2e over its entire lifecycle, from the cotton field to the last spin cycle. The mean is slightly higher at 5.56 kg, pulled up by a long tail of high-impact scenarios.

But the distribution is what makes this interesting. Ninety percent of T-shirts in our simulation fall between 3.8 and 7.8 kg CO2e. The lowest we observed was 2.3 kg: an organic cotton tee, made in Portugal with renewable energy, owned by a European who line-dries. The highest was 11.2 kg: conventional cotton-elastane blend, made in India, tumble-dried after every wash in the US.

To put 5.4 kg in perspective: it's roughly equivalent to driving 22 km in a petrol car, or charging a smartphone 660 times, or running a laptop for about 45 hours. One T-shirt. It doesn't sound like much until you consider that the world produces roughly 2 billion T-shirts per year.

Where Do the Emissions Come From? (It's Not What You Think)

If you've read anything about sustainable fashion, you probably assume the cotton is the problem. Conventional cotton farming uses pesticides, irrigation, and fertilizer, all carbon-intensive. Switching to organic cotton is marketed as the solution. And yes, organic cotton does have a significantly lower carbon footprint per kilogram.

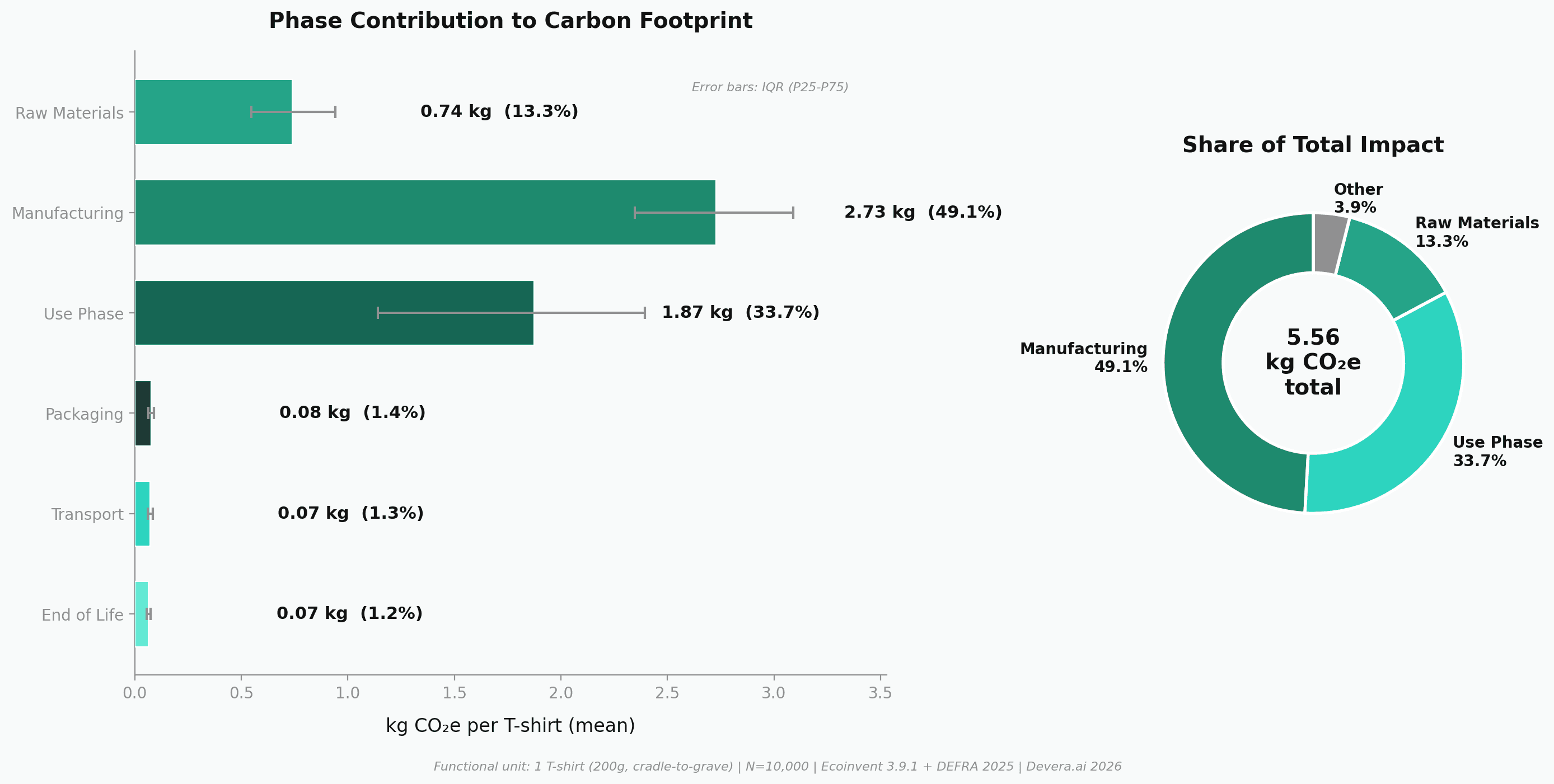

But here's the thing: raw materials account for only 13% of a T-shirt's total carbon footprint.

The dominant phase is manufacturing, at 49%. Nearly half of all emissions come from the factory. And the second biggest contributor is one that most sustainability conversations completely ignore: the use phase, at 34%. That's you, washing and drying the T-shirt over its lifetime.

Lifecycle Phase | Mean Impact (kg CO2e) | Share of Total |

|---|---|---|

Manufacturing | 2.73 | 49.1% |

Use Phase (washing, drying) | 1.87 | 33.7% |

Raw Materials | 0.74 | 13.3% |

Packaging | 0.08 | 1.4% |

Transport | 0.07 | 1.3% |

End of Life | 0.07 | 1.2% |

Together, packaging, transport, and end-of-life disposal add up to less than 4%. The narrative that shipping a T-shirt from China to Europe is the climate problem is, quite simply, wrong. Container ships are astonishingly efficient: moving a T-shirt 18,000 km across the ocean produces about 0.06 kg CO2e. That's less than the detergent you'll use to wash it.

The Hidden Emissions Inside a Textile Factory

When most people think "manufacturing emissions," they think electricity. A sewing machine plugged into the grid. A cutting table with overhead lights. And yes, electricity matters, especially in countries where the grid runs on coal.

But the real story is wet processing. Dyeing, finishing, and yarn preparation require enormous amounts of steam, hot water, and chemical baths. A dyeing vat needs to be heated to 60–100°C and maintained for hours. Finishing treatments require pressurized steam. These thermal processes account for 75–93% of a factory's emissions, and they're invisible if you only count electricity.

We used what we call the Full System Process EF approach: for each manufacturing process, we decompose the emission factor into a non-electric component (heat, steam, chemicals, fixed regardless of location) and an electric component (varies with the local grid). The difference is dramatic:

Factory Process | If You Only Count Electricity | Full System (Real Impact) |

|---|---|---|

Batch dyeing | 0.27 kg CO2e/kg | 4.07 kg CO2e/kg |

Finishing | 0.21 kg CO2e/kg | 1.59 kg CO2e/kg |

Spinning | 0.55 kg CO2e/kg | 1.85 + electricity |

Dyeing alone has a 15x higher real impact than its electricity-only figure suggests. This means any LCA study that only counts factory kWh is underestimating manufacturing emissions by 60–80%. It's one of the most common methodological mistakes in fashion sustainability reporting, and it explains why some published benchmarks seem unrealistically low.

Your Washing Machine Matters More Than the Cotton Field

Here's a number that might change how you think about your wardrobe: the use phase accounts for a third of a T-shirt's lifetime emissions. Every wash cycle, every tumble-dry, every time you run the iron, it all adds up over 35, 50, or 80 washes.

And the variation is enormous. The model shows it depends almost entirely on two factors: where you live (which determines your electricity grid's carbon intensity) and whether you use a tumble dryer.

European consumer, line-drying: ~1.0 kg CO2e over the garment's lifetime

American consumer, tumble-drying: ~3.5 kg CO2e, 3.5 times more

The tumble dryer is, kg for kg, the most carbon-intensive thing you can do to a T-shirt. A single dryer cycle uses about 2.8 kWh, nearly five times more than the washing machine. If you tumble-dry after every wash for 35 cycles, your share of that energy adds roughly 2 kg CO2e to the T-shirt's footprint. That's more than the entire raw material phase for conventional cotton.

This finding is consistent with research from WRAP (the UK's Waste and Resources Action Programme), which has long argued that consumer garment care is an underappreciated lever for reducing fashion's climate impact.

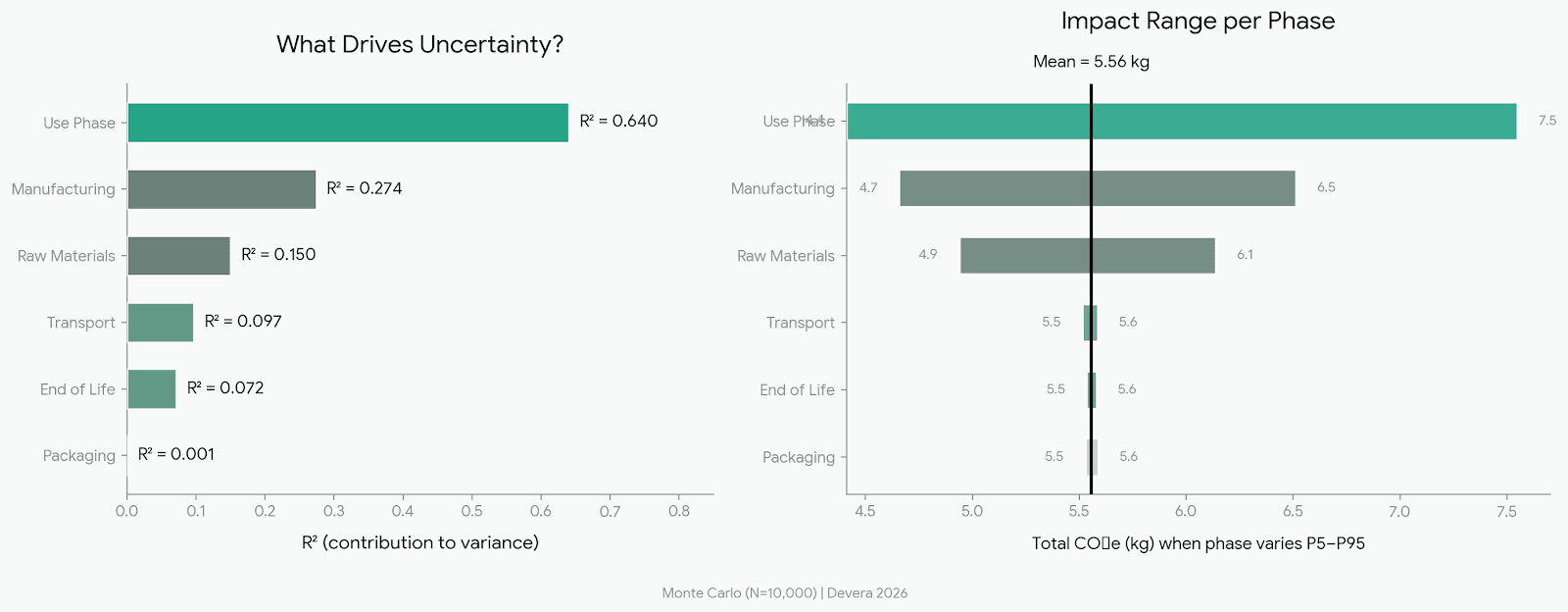

What Drives the Biggest Differences Between T-Shirts?

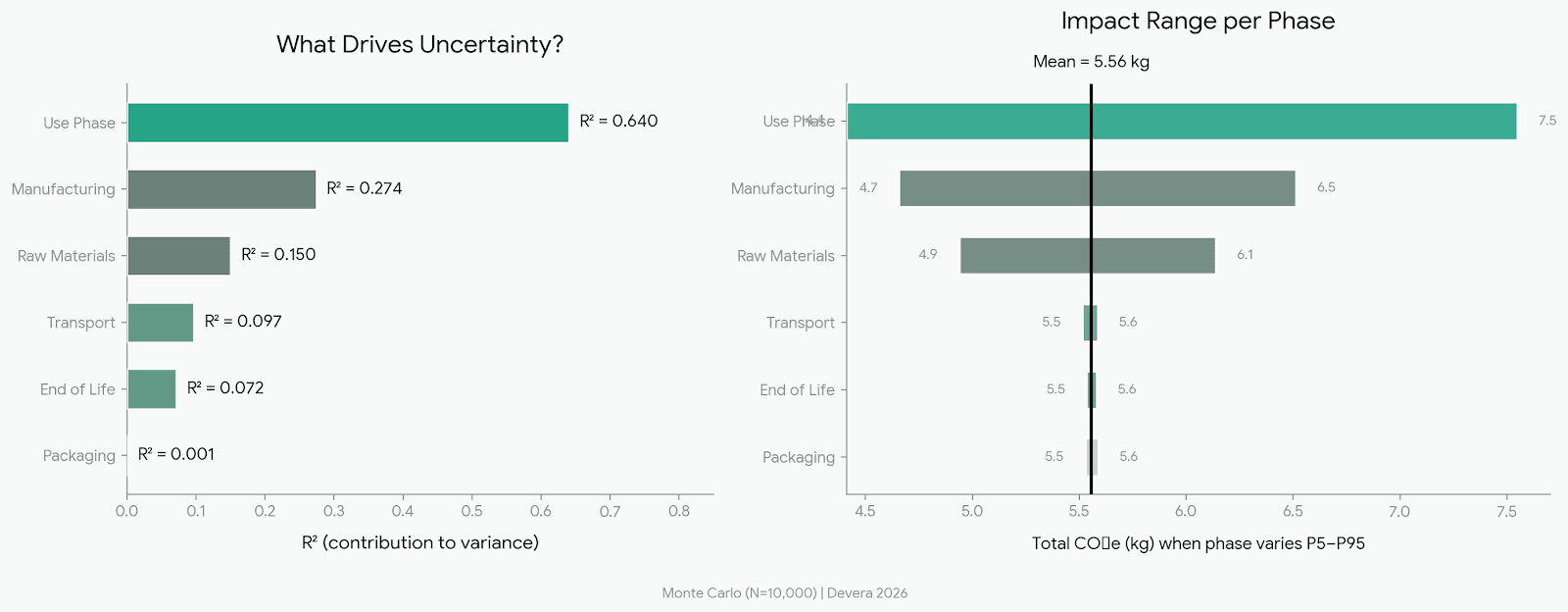

When you simulate 10,000 T-shirts, you can ask a statistical question: which parameter explains the most variation in the total? We measured this using R², the proportion of variance in total CO2e that each phase explains.

The results are striking. Consumer behavior explains 64% of the variation in a T-shirt's carbon footprint. That's not a typo. The difference between a European line-dryer and an American tumble-dryer, between 20 washes and 70 washes, between ironing and not ironing: these choices, aggregated over a garment's life, dominate the outcome.

Manufacturing location explains 27%. A factory in Portugal (grid carbon intensity: 0.34 kg/kWh, 45% renewable) produces a T-shirt with ~25% lower manufacturing emissions than one in Bangladesh (0.61 kg/kWh, 2% renewable). This isn't about labour costs or regulations, it's purely about the electricity grid.

Material choice explains 15%. Organic cotton vs conventional, recycled polyester vs virgin, these matter, but less than the marketing suggests. If you switch from conventional cotton to organic, you reduce the material phase by 85%. But the material phase is only 13% of the total, so the net impact on the full lifecycle is about 11%. That's meaningful, but it's not the revolution that organic cotton brands claim.

And then there's everything else. Packaging, transport, end-of-life: combined, they explain less than 4% of the variation. If your sustainability strategy is focused on recyclable poly bags and carbon-neutral shipping, you're optimizing the wrong 4%.

How Sustainable T-Shirt Brands Actually Compare

Theory is useful, but what do real products look like? We collected published carbon footprint data from nine T-shirts, ranging from certified sustainable brands to fast fashion, and benchmarked them against our simulation.

Product | CO2e | Score | Why It Scores This Way |

|---|---|---|---|

Minimalism Brand | 1.98 kg | A+ | Organic cotton, Portuguese factory with renewables, lightweight (200g) |

Continental EarthPositive | 2.3 kg | A+ | Organic cotton, factories powered by wind and solar. Carbon Trust certified. |

Aya (Peru) | 3.9 kg | A+ | Organic Pima cotton, local Peruvian supply chain, short distances, clean grid |

Harvest & Mill (USA) | 4.1 kg | A | Heirloom-coloured cotton eliminates dyeing entirely. Grown and sewn in the US. |

ISTO (Portugal) | 6.6 kg | D | GOTS organic, but significantly heavier garment increases all material/manufacturing phases |

Allbirds TrinoXO | 7.1 kg | D | Tree fibre + merino wool blend, innovative materials but both carry higher EFs than cotton |

Industry Average | 8.8 kg | E | Conventional cotton, Asian manufacturing, standard consumer behavior |

Carbonfact DB Median | 10.6 kg | E | EU PEF methodology on 50M+ products. Higher due to 267g avg weight and different method. |

Fast Fashion (US consumer) | 14.5 kg | E | Conventional cotton, Chinese coal grid, American tumble-drying. Worst-case scenario. |

The gap between best and worst is over 7x. A Minimalism Brand T-shirt at 1.98 kg produces roughly one-seventh the emissions of a fast-fashion equivalent. That's not a marginal difference, it's a fundamentally different product in terms of climate impact.

What separates the A+ brands from the rest? Three things that show up in every case: organic or low-impact fiber, manufacturing in countries with clean electricity grids (Portugal, Peru), and lightweight construction. Continental EarthPositive goes further by powering its factories directly with wind and solar, which effectively removes the grid dependency altogether.

An interesting case is ISTO. They use GOTS-certified organic cotton and manufacture in Portugal, on paper, a sustainability leader. But their T-shirt is significantly heavier than 200g, which increases every weight-dependent phase (materials, manufacturing, transport, end-of-life). It's a reminder that garment weight is a silent multiplier that rarely makes it into marketing copy.

Why Our Numbers Differ from Other Benchmarks

If you've seen figures like 8–10 kg elsewhere, you might wonder why our median is 5.4. The differences are real but explainable:

Carbonfact reports a median of 10.6 kg across their database of 50 million+ products, but their average garment weighs 267g (33% heavier than our 200g reference) and they use the EU Product Environmental Footprint methodology, which systematically produces higher values. Wang et al. (2015) found 8.77 kg for a Chinese cotton shirt, but used higher cotton emission factors and modelled a heavier garment.

This is normal in LCA. Methodology choices (system boundaries, data sources, allocation rules) genuinely change results. What matters is not that everyone agrees on one number, but that each study is internally consistent and transparent about its assumptions. Ours is.

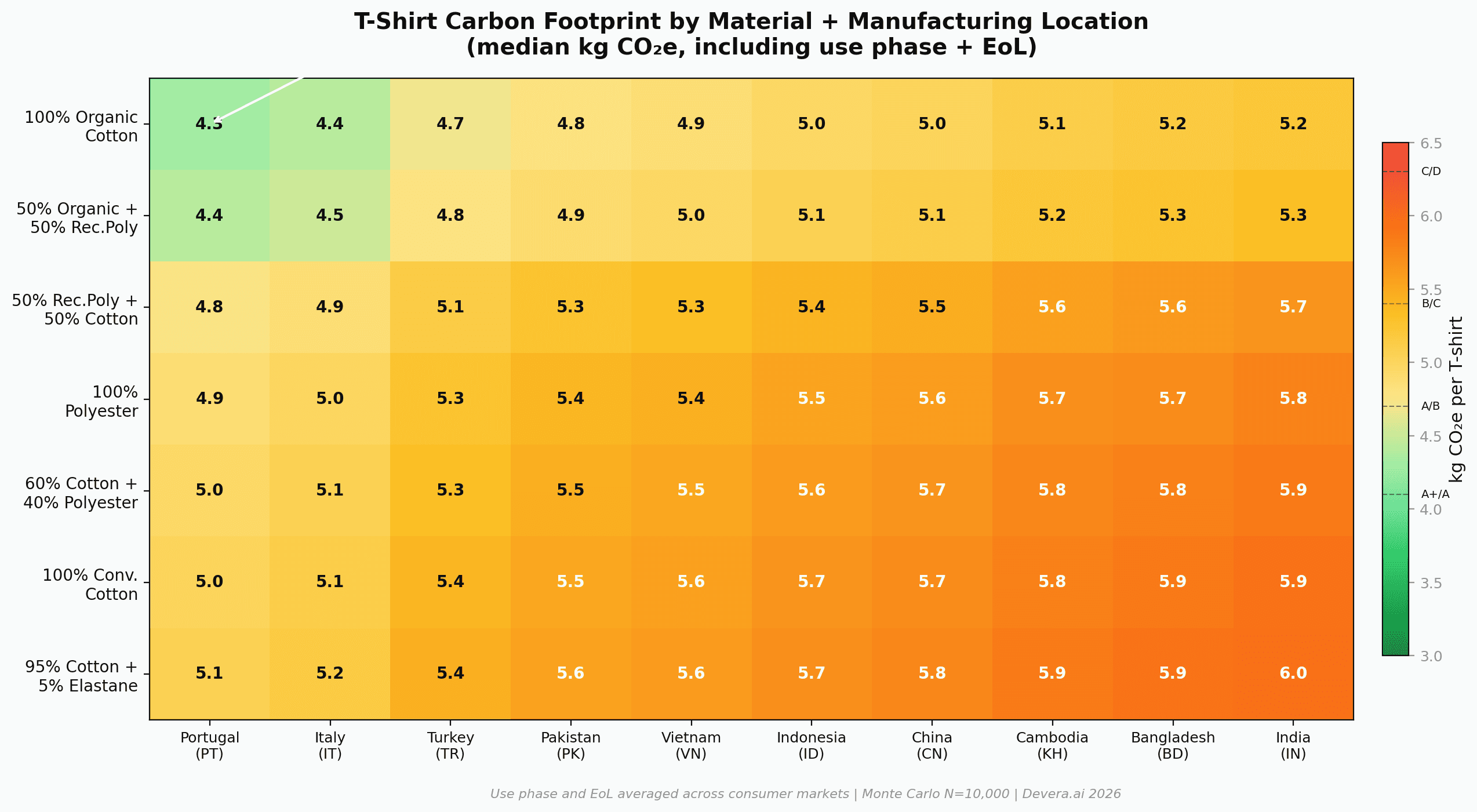

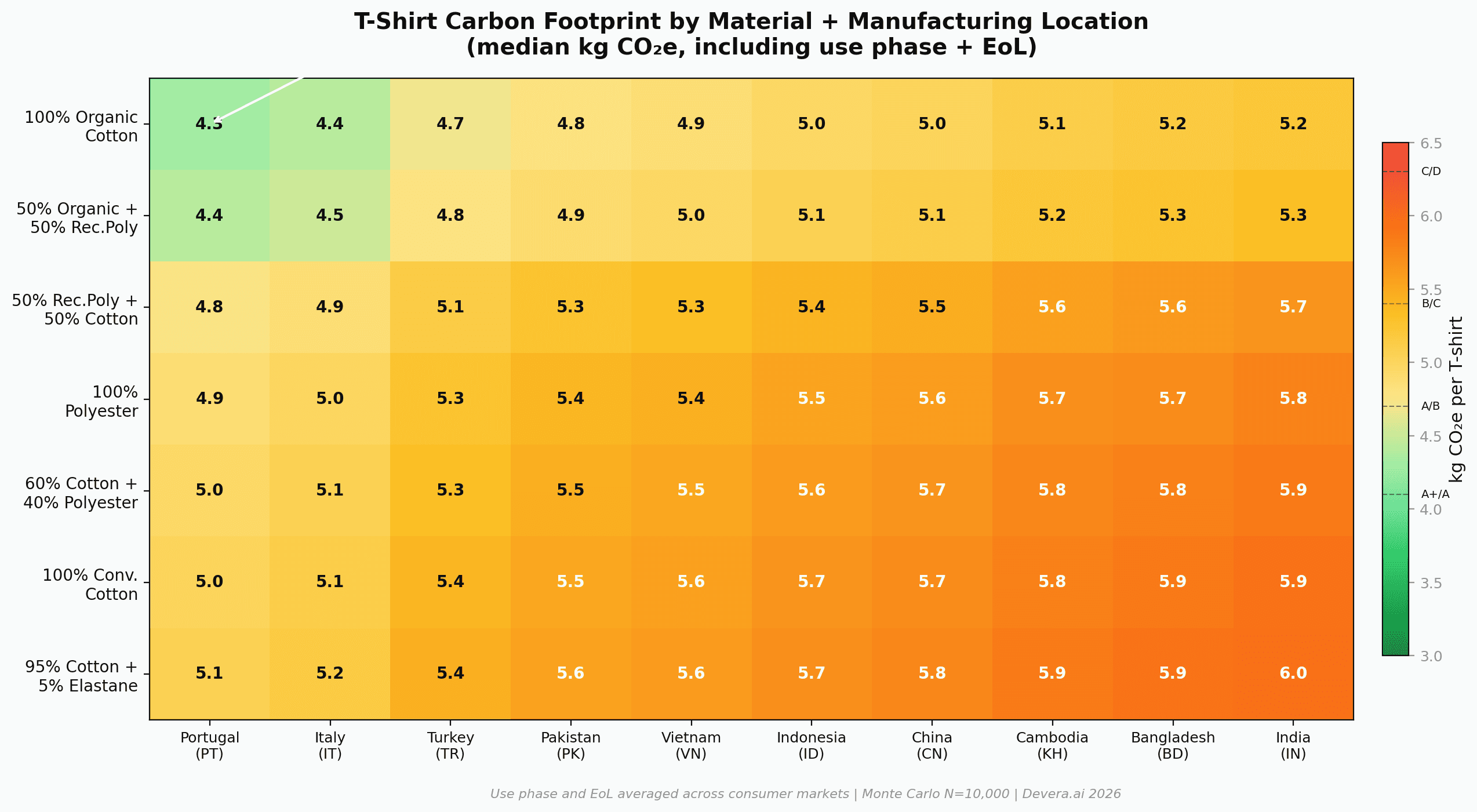

Supply Chain Decisions: Material Choice Meets Factory Location

One of the most useful outputs of the simulation is a matrix showing how material choice and manufacturing location interact. This is actionable data for sourcing managers: it tells you exactly which combinations produce the lowest and highest footprints.

The best combination, organic cotton manufactured in Portugal, averages about 4.2 kg total. The worst, conventional cotton-elastane blend manufactured in India or Bangladesh, comes in around 6.0 kg. That's a 43% difference driven entirely by supply chain decisions that happen before a single consumer touches the product.

The heatmap reveals two clear patterns. First, material choice creates vertical bands: organic and recycled materials score lower regardless of where they're made. A recycled polyester tee made in Bangladesh still beats a conventional cotton tee made in Portugal. Second, manufacturing location creates horizontal gradients: European locations (Portugal at 0.34, Italy at 0.35 kg/kWh) consistently outperform Asian ones (India at 0.71, Bangladesh at 0.61) due to cleaner grids.

But the most important insight is that these two levers compound. Choosing organic cotton and manufacturing in Portugal saves more than the sum of each change individually, because the weight reduction from lighter organic fiber also reduces the manufacturing energy needed per garment.

A Scoring System for T-Shirt Carbon Footprints

Based on the simulation distribution, we propose a simple A+ to E scoring system. The thresholds are set at percentile boundaries, so each grade represents a meaningful segment of the market:

Score | Range | Percentile | What It Means |

|---|---|---|---|

A+ | < 4.1 kg | Top 10% | Best in class. Organic/recycled materials, renewable-powered factory, lightweight design. |

A | 4.1 – 4.7 kg | 10–25% | Excellent. Either sustainable materials or efficient manufacturing, ideally both. |

B | 4.7 – 5.4 kg | 25–50% | Good. Below the median. Some sustainability measures in place. |

C | 5.4 – 6.3 kg | 50–75% | Average. Typical industry practice. No particular sustainability focus. |

D | 6.3 – 7.2 kg | 75–90% | Below average. Conventional materials, carbon-heavy manufacturing grid. |

E | > 7.2 kg | Bottom 10% | High impact. Heavy garment, dirty grid, no sustainability measures. |

These thresholds are descriptive, not prescriptive: they tell you where a T-shirt sits relative to the simulated market. An A+ doesn't mean "zero impact." It means your product is in the top 10% of what's possible with current technology and supply chains. There's still a long way to go.

What Can Brands Actually Do? (Ranked by Impact)

The data points to three levers, in order of how much they actually move the needle:

1. Decarbonize Manufacturing (49% of the footprint)

This is the biggest lever and the one most brands aren't talking about. If your factory is in Bangladesh (grid: 0.61 kg/kWh, 2% renewable), nearly half of your T-shirt's footprint comes from the factory floor, mostly from heating water and generating steam for dyeing and finishing.

Three concrete actions: install on-site solar or purchase renewable energy certificates for the factory. Invest in heat recovery systems that capture waste heat from dyeing baths. Switch from coal-fired boilers to natural gas or biomass. Continental EarthPositive demonstrated that powering factories with 100% renewable energy can reduce the production footprint by up to 90%.

Alternatively, consider manufacturing in countries with cleaner grids. A T-shirt made in Portugal (0.34, 45% renewable) has roughly 25% lower manufacturing emissions than one from India or Bangladesh. This isn't about reshoring for political reasons, it's a direct carbon calculation.

2. Help Consumers Reduce Their Impact (34% of the footprint)

This is the hardest lever because it's out of the brand's direct control. But the data is clear: consumer washing and drying habits are the single biggest source of uncertainty in a T-shirt's footprint.

What brands can do: print clear care instructions that recommend cold-water washing and line drying. Some brands (like Allbirds) already label products with their carbon footprint, and extending this to include "impact of your care choices" would be powerful. Most importantly, design for durability. A T-shirt that survives 60 washes instead of 25 has a lower per-wear footprint even if the production emissions are identical.

3. Choose Lower-Impact Materials (13% of the footprint)

Material choice matters, it's just not the silver bullet that marketing departments want it to be. Organic cotton (0.63 kg CO2e/kg) has an 85% lower emission factor than conventional (4.13). Recycled polyester (1.67) is 52% lower than virgin (3.50). These are significant reductions within the material phase.

But the material phase is 13% of the total lifecycle. An 85% reduction in 13% is an 11% reduction overall. Meaningful? Yes. Transformative? Not on its own. The brands that truly score A+ combine material choice with manufacturing decarbonization, and that combination is what creates the 64–73% gap between sustainable leaders and the industry average.

Methodology and Data Sources

Full transparency on how this benchmark was built:

Simulation type: Monte Carlo, 10,000 iterations. Sample size justified by Heijungs (2020), who showed that 10,000 runs produce stable percentile estimates in comparative probabilistic LCA.

Functional unit: 1 T-shirt, cradle-to-grave, from raw material extraction through manufacturing, distribution, consumer use (washing/drying/ironing over full garment lifetime), and final disposal (landfill, incineration, or recycling).

Reference weight: 200g (medium adult T-shirt). Weight sampled from a normal distribution (SD 30g, clipped at 120–320g).

Emission factor sources:

Ecoinvent 3.9.1: material EFs, manufacturing process energy, country-specific electricity grids

DEFRA 2025: UK Government GHG conversion factors for transport, packaging, waste treatment, fuels

EEA 2023: European textile recovery and recycling rates

Textile Exchange 2023: global fiber market shares for scenario probabilities

Manufacturing model: Full System Process EF, which decomposes each factory process into a non-electric component (heat, steam, chemicals) and an electric component (varies by country grid). Formula: process_CO2e = non_electric + (electricity_kWh × grid_EF × (1 - renewable%))

Probability distributions: Lognormal for emission factors (standard Ecoinvent convention), Triangular for transport distances and wash counts, Normal for garment weight.

Reference products: Published data from Continental EarthPositive (Carbon Trust / PAS 2050), Arbor 2024, Allbirds, Carbonfact 2024, Wang et al. 2015.

References

ecoinvent Centre. ecoinvent database v3.9.1. Zurich, Switzerland, 2022.

ecoinvent.orgUK DESNZ / DEFRA. Greenhouse gas reporting: conversion factors 2025. UK Government, June 2025.

gov.uk/government/publications/greenhouse-gas-reporting-conversion-factors-2025ISO. ISO 14040:2006: Environmental management, Life cycle assessment, Principles and framework. Geneva, 2006.

iso.org/standard/37456.htmlWang, C., Wang, L., Liu, X., Du, C., Ding, D., Jia, J., Yan, Y. & Wu, G. (2015). "Carbon footprint of textile throughout its life cycle: a case study of Chinese cotton shirts." Journal of Cleaner Production, 108, 464–475.

doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.05.127Ruzgar, A., Taskin, E.G., Guney, S. & Cambaz, N. (2018). "Life Cycle Assessment of a Cotton T-Shirt." Proc. XIVth International Izmir Textile and Apparel Symposium.

ResearchGateCarbonfact. "The Carbon Footprint of a T-Shirt." 2024.

carbonfact.com/carbon-footprint/t-shirtTextile Exchange. Materials Market Report 2023. November 2023.

textileexchange.orgHeijungs, R. (2020). "On the number of Monte Carlo runs in comparative probabilistic LCA." Int J Life Cycle Assess, 25, 394–402.

doi.org/10.1007/s11367-019-01698-4European Environment Agency. Management of used and waste textiles in Europe's circular economy. EEA, 2023.

eea.europa.euWRAP. Sustainable Clothing Guide. Banbury, UK.

wrap.ngoContinental Clothing. EarthPositive: Sustainability. Carbon Trust / PAS 2050.

continentalclothing.com/about/earthpositiveNesser, A. / Arbor. "6 Shirts, 3 Countries: Analyzing the Carbon Footprint of Clean Fashion." August 2024.

arbor.eco/blog/6-shirts-3-countriesAllbirds, Inc. "What's In a Footprint?" Product carbon footprint methodology.

allbirds.com/pages/footprintEurostat. Packaging waste statistics. European Commission.

ec.europa.eu/eurostatEuropean Commission. Regulation (EU) 2019/2023: Ecodesign requirements for household washing machines.

eur-lex.europa.euBSI / Carbon Trust / DEFRA. PAS 2050:2011: Specification for the assessment of the life cycle greenhouse gas emissions of goods and services. London, 2011.

PAS 2050 Factsheet (GHG Protocol)

This benchmark was produced by Devera, a platform for automated Life Cycle Assessment. Every emission factor is verified against Ecoinvent 3.9.1 and DEFRA 2025, no invented numbers, full traceability. Want to know the carbon footprint of your product? Try Devera for free.

T-Shirt Carbon Benchmark: 10,000 Simulations Reveal What Really Matters

Everyone talks about sustainable cotton. But the data tells a completely different story about where T-shirt emissions actually come from, and it's not what most brands want you to focus on.

Ask ten sustainability experts how much carbon a T-shirt produces and you'll get ten different answers. Some say 2 kg. Others say 15. A few will confidently quote "about 8" without telling you where that number comes from.

The truth is, there isn't a single number. The carbon footprint of a T-shirt depends on what it's made of, where it was manufactured, how it gets to you, and, crucially, how you wash it for the next three years. The problem with most benchmarks is that they pick one scenario and present it as the answer. A conventional cotton T-shirt made in China, washed 25 times, line-dried in Europe. Done. 8.77 kg. Next question.

But that single number hides a distribution. It ignores the organic cotton tee from Portugal that comes in at under 2 kg. It ignores the fast-fashion tee that gets tumble-dried twice a week in Texas and racks up 14 kg. It ignores the fact that what you do after you buy a T-shirt matters more than what it's made of.

So we decided to model the full picture. Not one T-shirt, ten thousand of them.

Key Findings

Median carbon footprint: 5.4 kg CO2e per T-shirt (cradle-to-grave)

90% range: 3.8 to 7.8 kg CO2e

#1 contributor: Manufacturing (49%), mostly heat and steam, not electricity

#1 source of uncertainty: Consumer behavior (64%), tumble drying is the single worst thing you can do

Sustainable brands vs fast fashion: 64–73% lower footprint. The gap is real.

How We Built This Benchmark

We used Monte Carlo simulation, the same statistical technique used by climate scientists, financial risk analysts, and pharmaceutical researchers when a single answer isn't enough. The idea is simple: instead of calculating one T-shirt, you calculate thousands, each with slightly different parameters drawn from realistic probability distributions.

Each of our 10,000 simulated T-shirts was assigned a random combination of materials, factory location, consumer market, garment weight, number of wash cycles, and disposal pathway. Not arbitrary random, weighted by real-world market data. A T-shirt is 6x more likely to be made in China than in Portugal, because that's what global trade data tells us. It's 3x more likely to be 100% cotton than polyester, because that's what Textile Exchange reports.

Every emission factor in the model is traceable. Material carbon intensities come from Ecoinvent 3.9.1, the most widely used LCA database in the world. Transport and waste factors come from DEFRA 2025, the UK Government's official greenhouse gas conversion factors. The methodology follows ISO 14040/44, the international standard for Life Cycle Assessment.

No invented numbers. No "industry estimates." Every value can be checked against its source.

What Does the Carbon Footprint of a T-Shirt Actually Look Like?

The headline number: the median T-shirt produces 5.4 kg of CO2e over its entire lifecycle, from the cotton field to the last spin cycle. The mean is slightly higher at 5.56 kg, pulled up by a long tail of high-impact scenarios.

But the distribution is what makes this interesting. Ninety percent of T-shirts in our simulation fall between 3.8 and 7.8 kg CO2e. The lowest we observed was 2.3 kg: an organic cotton tee, made in Portugal with renewable energy, owned by a European who line-dries. The highest was 11.2 kg: conventional cotton-elastane blend, made in India, tumble-dried after every wash in the US.

To put 5.4 kg in perspective: it's roughly equivalent to driving 22 km in a petrol car, or charging a smartphone 660 times, or running a laptop for about 45 hours. One T-shirt. It doesn't sound like much until you consider that the world produces roughly 2 billion T-shirts per year.

Where Do the Emissions Come From? (It's Not What You Think)

If you've read anything about sustainable fashion, you probably assume the cotton is the problem. Conventional cotton farming uses pesticides, irrigation, and fertilizer, all carbon-intensive. Switching to organic cotton is marketed as the solution. And yes, organic cotton does have a significantly lower carbon footprint per kilogram.

But here's the thing: raw materials account for only 13% of a T-shirt's total carbon footprint.

The dominant phase is manufacturing, at 49%. Nearly half of all emissions come from the factory. And the second biggest contributor is one that most sustainability conversations completely ignore: the use phase, at 34%. That's you, washing and drying the T-shirt over its lifetime.

Lifecycle Phase | Mean Impact (kg CO2e) | Share of Total |

|---|---|---|

Manufacturing | 2.73 | 49.1% |

Use Phase (washing, drying) | 1.87 | 33.7% |

Raw Materials | 0.74 | 13.3% |

Packaging | 0.08 | 1.4% |

Transport | 0.07 | 1.3% |

End of Life | 0.07 | 1.2% |

Together, packaging, transport, and end-of-life disposal add up to less than 4%. The narrative that shipping a T-shirt from China to Europe is the climate problem is, quite simply, wrong. Container ships are astonishingly efficient: moving a T-shirt 18,000 km across the ocean produces about 0.06 kg CO2e. That's less than the detergent you'll use to wash it.

The Hidden Emissions Inside a Textile Factory

When most people think "manufacturing emissions," they think electricity. A sewing machine plugged into the grid. A cutting table with overhead lights. And yes, electricity matters, especially in countries where the grid runs on coal.

But the real story is wet processing. Dyeing, finishing, and yarn preparation require enormous amounts of steam, hot water, and chemical baths. A dyeing vat needs to be heated to 60–100°C and maintained for hours. Finishing treatments require pressurized steam. These thermal processes account for 75–93% of a factory's emissions, and they're invisible if you only count electricity.

We used what we call the Full System Process EF approach: for each manufacturing process, we decompose the emission factor into a non-electric component (heat, steam, chemicals, fixed regardless of location) and an electric component (varies with the local grid). The difference is dramatic:

Factory Process | If You Only Count Electricity | Full System (Real Impact) |

|---|---|---|

Batch dyeing | 0.27 kg CO2e/kg | 4.07 kg CO2e/kg |

Finishing | 0.21 kg CO2e/kg | 1.59 kg CO2e/kg |

Spinning | 0.55 kg CO2e/kg | 1.85 + electricity |

Dyeing alone has a 15x higher real impact than its electricity-only figure suggests. This means any LCA study that only counts factory kWh is underestimating manufacturing emissions by 60–80%. It's one of the most common methodological mistakes in fashion sustainability reporting, and it explains why some published benchmarks seem unrealistically low.

Your Washing Machine Matters More Than the Cotton Field

Here's a number that might change how you think about your wardrobe: the use phase accounts for a third of a T-shirt's lifetime emissions. Every wash cycle, every tumble-dry, every time you run the iron, it all adds up over 35, 50, or 80 washes.

And the variation is enormous. The model shows it depends almost entirely on two factors: where you live (which determines your electricity grid's carbon intensity) and whether you use a tumble dryer.

European consumer, line-drying: ~1.0 kg CO2e over the garment's lifetime

American consumer, tumble-drying: ~3.5 kg CO2e, 3.5 times more

The tumble dryer is, kg for kg, the most carbon-intensive thing you can do to a T-shirt. A single dryer cycle uses about 2.8 kWh, nearly five times more than the washing machine. If you tumble-dry after every wash for 35 cycles, your share of that energy adds roughly 2 kg CO2e to the T-shirt's footprint. That's more than the entire raw material phase for conventional cotton.

This finding is consistent with research from WRAP (the UK's Waste and Resources Action Programme), which has long argued that consumer garment care is an underappreciated lever for reducing fashion's climate impact.

What Drives the Biggest Differences Between T-Shirts?

When you simulate 10,000 T-shirts, you can ask a statistical question: which parameter explains the most variation in the total? We measured this using R², the proportion of variance in total CO2e that each phase explains.

The results are striking. Consumer behavior explains 64% of the variation in a T-shirt's carbon footprint. That's not a typo. The difference between a European line-dryer and an American tumble-dryer, between 20 washes and 70 washes, between ironing and not ironing: these choices, aggregated over a garment's life, dominate the outcome.

Manufacturing location explains 27%. A factory in Portugal (grid carbon intensity: 0.34 kg/kWh, 45% renewable) produces a T-shirt with ~25% lower manufacturing emissions than one in Bangladesh (0.61 kg/kWh, 2% renewable). This isn't about labour costs or regulations, it's purely about the electricity grid.

Material choice explains 15%. Organic cotton vs conventional, recycled polyester vs virgin, these matter, but less than the marketing suggests. If you switch from conventional cotton to organic, you reduce the material phase by 85%. But the material phase is only 13% of the total, so the net impact on the full lifecycle is about 11%. That's meaningful, but it's not the revolution that organic cotton brands claim.

And then there's everything else. Packaging, transport, end-of-life: combined, they explain less than 4% of the variation. If your sustainability strategy is focused on recyclable poly bags and carbon-neutral shipping, you're optimizing the wrong 4%.

How Sustainable T-Shirt Brands Actually Compare

Theory is useful, but what do real products look like? We collected published carbon footprint data from nine T-shirts, ranging from certified sustainable brands to fast fashion, and benchmarked them against our simulation.

Product | CO2e | Score | Why It Scores This Way |

|---|---|---|---|

Minimalism Brand | 1.98 kg | A+ | Organic cotton, Portuguese factory with renewables, lightweight (200g) |

Continental EarthPositive | 2.3 kg | A+ | Organic cotton, factories powered by wind and solar. Carbon Trust certified. |

Aya (Peru) | 3.9 kg | A+ | Organic Pima cotton, local Peruvian supply chain, short distances, clean grid |

Harvest & Mill (USA) | 4.1 kg | A | Heirloom-coloured cotton eliminates dyeing entirely. Grown and sewn in the US. |

ISTO (Portugal) | 6.6 kg | D | GOTS organic, but significantly heavier garment increases all material/manufacturing phases |

Allbirds TrinoXO | 7.1 kg | D | Tree fibre + merino wool blend, innovative materials but both carry higher EFs than cotton |

Industry Average | 8.8 kg | E | Conventional cotton, Asian manufacturing, standard consumer behavior |

Carbonfact DB Median | 10.6 kg | E | EU PEF methodology on 50M+ products. Higher due to 267g avg weight and different method. |

Fast Fashion (US consumer) | 14.5 kg | E | Conventional cotton, Chinese coal grid, American tumble-drying. Worst-case scenario. |

The gap between best and worst is over 7x. A Minimalism Brand T-shirt at 1.98 kg produces roughly one-seventh the emissions of a fast-fashion equivalent. That's not a marginal difference, it's a fundamentally different product in terms of climate impact.

What separates the A+ brands from the rest? Three things that show up in every case: organic or low-impact fiber, manufacturing in countries with clean electricity grids (Portugal, Peru), and lightweight construction. Continental EarthPositive goes further by powering its factories directly with wind and solar, which effectively removes the grid dependency altogether.

An interesting case is ISTO. They use GOTS-certified organic cotton and manufacture in Portugal, on paper, a sustainability leader. But their T-shirt is significantly heavier than 200g, which increases every weight-dependent phase (materials, manufacturing, transport, end-of-life). It's a reminder that garment weight is a silent multiplier that rarely makes it into marketing copy.

Why Our Numbers Differ from Other Benchmarks

If you've seen figures like 8–10 kg elsewhere, you might wonder why our median is 5.4. The differences are real but explainable:

Carbonfact reports a median of 10.6 kg across their database of 50 million+ products, but their average garment weighs 267g (33% heavier than our 200g reference) and they use the EU Product Environmental Footprint methodology, which systematically produces higher values. Wang et al. (2015) found 8.77 kg for a Chinese cotton shirt, but used higher cotton emission factors and modelled a heavier garment.

This is normal in LCA. Methodology choices (system boundaries, data sources, allocation rules) genuinely change results. What matters is not that everyone agrees on one number, but that each study is internally consistent and transparent about its assumptions. Ours is.

Supply Chain Decisions: Material Choice Meets Factory Location

One of the most useful outputs of the simulation is a matrix showing how material choice and manufacturing location interact. This is actionable data for sourcing managers: it tells you exactly which combinations produce the lowest and highest footprints.

The best combination, organic cotton manufactured in Portugal, averages about 4.2 kg total. The worst, conventional cotton-elastane blend manufactured in India or Bangladesh, comes in around 6.0 kg. That's a 43% difference driven entirely by supply chain decisions that happen before a single consumer touches the product.

The heatmap reveals two clear patterns. First, material choice creates vertical bands: organic and recycled materials score lower regardless of where they're made. A recycled polyester tee made in Bangladesh still beats a conventional cotton tee made in Portugal. Second, manufacturing location creates horizontal gradients: European locations (Portugal at 0.34, Italy at 0.35 kg/kWh) consistently outperform Asian ones (India at 0.71, Bangladesh at 0.61) due to cleaner grids.

But the most important insight is that these two levers compound. Choosing organic cotton and manufacturing in Portugal saves more than the sum of each change individually, because the weight reduction from lighter organic fiber also reduces the manufacturing energy needed per garment.

A Scoring System for T-Shirt Carbon Footprints

Based on the simulation distribution, we propose a simple A+ to E scoring system. The thresholds are set at percentile boundaries, so each grade represents a meaningful segment of the market:

Score | Range | Percentile | What It Means |

|---|---|---|---|

A+ | < 4.1 kg | Top 10% | Best in class. Organic/recycled materials, renewable-powered factory, lightweight design. |

A | 4.1 – 4.7 kg | 10–25% | Excellent. Either sustainable materials or efficient manufacturing, ideally both. |

B | 4.7 – 5.4 kg | 25–50% | Good. Below the median. Some sustainability measures in place. |

C | 5.4 – 6.3 kg | 50–75% | Average. Typical industry practice. No particular sustainability focus. |

D | 6.3 – 7.2 kg | 75–90% | Below average. Conventional materials, carbon-heavy manufacturing grid. |

E | > 7.2 kg | Bottom 10% | High impact. Heavy garment, dirty grid, no sustainability measures. |

These thresholds are descriptive, not prescriptive: they tell you where a T-shirt sits relative to the simulated market. An A+ doesn't mean "zero impact." It means your product is in the top 10% of what's possible with current technology and supply chains. There's still a long way to go.

What Can Brands Actually Do? (Ranked by Impact)

The data points to three levers, in order of how much they actually move the needle:

1. Decarbonize Manufacturing (49% of the footprint)

This is the biggest lever and the one most brands aren't talking about. If your factory is in Bangladesh (grid: 0.61 kg/kWh, 2% renewable), nearly half of your T-shirt's footprint comes from the factory floor, mostly from heating water and generating steam for dyeing and finishing.

Three concrete actions: install on-site solar or purchase renewable energy certificates for the factory. Invest in heat recovery systems that capture waste heat from dyeing baths. Switch from coal-fired boilers to natural gas or biomass. Continental EarthPositive demonstrated that powering factories with 100% renewable energy can reduce the production footprint by up to 90%.

Alternatively, consider manufacturing in countries with cleaner grids. A T-shirt made in Portugal (0.34, 45% renewable) has roughly 25% lower manufacturing emissions than one from India or Bangladesh. This isn't about reshoring for political reasons, it's a direct carbon calculation.

2. Help Consumers Reduce Their Impact (34% of the footprint)

This is the hardest lever because it's out of the brand's direct control. But the data is clear: consumer washing and drying habits are the single biggest source of uncertainty in a T-shirt's footprint.

What brands can do: print clear care instructions that recommend cold-water washing and line drying. Some brands (like Allbirds) already label products with their carbon footprint, and extending this to include "impact of your care choices" would be powerful. Most importantly, design for durability. A T-shirt that survives 60 washes instead of 25 has a lower per-wear footprint even if the production emissions are identical.

3. Choose Lower-Impact Materials (13% of the footprint)

Material choice matters, it's just not the silver bullet that marketing departments want it to be. Organic cotton (0.63 kg CO2e/kg) has an 85% lower emission factor than conventional (4.13). Recycled polyester (1.67) is 52% lower than virgin (3.50). These are significant reductions within the material phase.

But the material phase is 13% of the total lifecycle. An 85% reduction in 13% is an 11% reduction overall. Meaningful? Yes. Transformative? Not on its own. The brands that truly score A+ combine material choice with manufacturing decarbonization, and that combination is what creates the 64–73% gap between sustainable leaders and the industry average.

Methodology and Data Sources

Full transparency on how this benchmark was built:

Simulation type: Monte Carlo, 10,000 iterations. Sample size justified by Heijungs (2020), who showed that 10,000 runs produce stable percentile estimates in comparative probabilistic LCA.

Functional unit: 1 T-shirt, cradle-to-grave, from raw material extraction through manufacturing, distribution, consumer use (washing/drying/ironing over full garment lifetime), and final disposal (landfill, incineration, or recycling).

Reference weight: 200g (medium adult T-shirt). Weight sampled from a normal distribution (SD 30g, clipped at 120–320g).

Emission factor sources:

Ecoinvent 3.9.1: material EFs, manufacturing process energy, country-specific electricity grids

DEFRA 2025: UK Government GHG conversion factors for transport, packaging, waste treatment, fuels

EEA 2023: European textile recovery and recycling rates

Textile Exchange 2023: global fiber market shares for scenario probabilities

Manufacturing model: Full System Process EF, which decomposes each factory process into a non-electric component (heat, steam, chemicals) and an electric component (varies by country grid). Formula: process_CO2e = non_electric + (electricity_kWh × grid_EF × (1 - renewable%))

Probability distributions: Lognormal for emission factors (standard Ecoinvent convention), Triangular for transport distances and wash counts, Normal for garment weight.

Reference products: Published data from Continental EarthPositive (Carbon Trust / PAS 2050), Arbor 2024, Allbirds, Carbonfact 2024, Wang et al. 2015.

References

ecoinvent Centre. ecoinvent database v3.9.1. Zurich, Switzerland, 2022.

ecoinvent.orgUK DESNZ / DEFRA. Greenhouse gas reporting: conversion factors 2025. UK Government, June 2025.

gov.uk/government/publications/greenhouse-gas-reporting-conversion-factors-2025ISO. ISO 14040:2006: Environmental management, Life cycle assessment, Principles and framework. Geneva, 2006.

iso.org/standard/37456.htmlWang, C., Wang, L., Liu, X., Du, C., Ding, D., Jia, J., Yan, Y. & Wu, G. (2015). "Carbon footprint of textile throughout its life cycle: a case study of Chinese cotton shirts." Journal of Cleaner Production, 108, 464–475.

doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.05.127Ruzgar, A., Taskin, E.G., Guney, S. & Cambaz, N. (2018). "Life Cycle Assessment of a Cotton T-Shirt." Proc. XIVth International Izmir Textile and Apparel Symposium.

ResearchGateCarbonfact. "The Carbon Footprint of a T-Shirt." 2024.

carbonfact.com/carbon-footprint/t-shirtTextile Exchange. Materials Market Report 2023. November 2023.

textileexchange.orgHeijungs, R. (2020). "On the number of Monte Carlo runs in comparative probabilistic LCA." Int J Life Cycle Assess, 25, 394–402.

doi.org/10.1007/s11367-019-01698-4European Environment Agency. Management of used and waste textiles in Europe's circular economy. EEA, 2023.

eea.europa.euWRAP. Sustainable Clothing Guide. Banbury, UK.

wrap.ngoContinental Clothing. EarthPositive: Sustainability. Carbon Trust / PAS 2050.

continentalclothing.com/about/earthpositiveNesser, A. / Arbor. "6 Shirts, 3 Countries: Analyzing the Carbon Footprint of Clean Fashion." August 2024.

arbor.eco/blog/6-shirts-3-countriesAllbirds, Inc. "What's In a Footprint?" Product carbon footprint methodology.

allbirds.com/pages/footprintEurostat. Packaging waste statistics. European Commission.

ec.europa.eu/eurostatEuropean Commission. Regulation (EU) 2019/2023: Ecodesign requirements for household washing machines.

eur-lex.europa.euBSI / Carbon Trust / DEFRA. PAS 2050:2011: Specification for the assessment of the life cycle greenhouse gas emissions of goods and services. London, 2011.

PAS 2050 Factsheet (GHG Protocol)

This benchmark was produced by Devera, a platform for automated Life Cycle Assessment. Every emission factor is verified against Ecoinvent 3.9.1 and DEFRA 2025, no invented numbers, full traceability. Want to know the carbon footprint of your product? Try Devera for free.